Cyrus McCrimmon

Rydberg on May 1 at the REDI Lab presentations

When I first stepped into the REDI Lab program, I thought I had a solid understanding of who I was and what I liked. From a young age, I had always enjoyed building things and drawing them, mixing technical precision with creative freedom. Engineering and art were my “things,” and I didn’t think much beyond that. I knew what I liked, but I had never asked myself why. REDI Lab changed that.

At the start, I approached the program with the mindset of a builder. I had a rough idea of a machine I wanted to create, something that could perhaps automate drawing or translate digital designs into physical motion. It felt like a perfect intersection of mechanics and creativity, but the purpose behind it was still vague. It wasn’t until I reflected on my motivations, something REDI Lab encourages deeply, that I realized the answer had been with me all along: my grandfather.

Growing up, he spent countless hours giving me art lessons and teaching me the beauty in design. He was an art professor at the Pratt Institute and an engineer in his earlier life. I now see that my love for engineering and art isn’t just a coincidence — it’s a legacy. REDI Lab helped me make that connection, turning my interests into something meaningful, something rooted in family and memory.

But realization alone doesn’t build machines. As the weeks progressed, I hit walls, hard ones. Balancing my project with the regular demands of school became a daily struggle. It wasn’t easy shifting gears from academic assignments to late-night prototyping sessions, and more than once I questioned if I could keep up with both. There were moments where I felt like I was letting both sides down, the student and the creator.

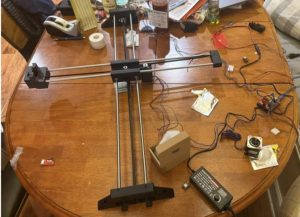

On top of that, the machine itself refused to cooperate. Motors misfired, code bugged out, wires tangled like spaghetti. Every small win seemed to be followed by a setback. I had envisioned this elegant, graceful tool that merged technology and aesthetics, but what I had looked more like a mess of scrap and wishful thinking.

REDI Lab’s structure, though, made space for struggle. Instead of seeing failure as the end, it became part of the process, something to reflect on and grow through. Mentorship from teachers and feedback from peers helped me take a step back, recalibrate, and approach the problems differently. I stopped trying to force the project to work and started listening to what it was teaching me.

In the final presentation, my machine wasn’t flawless, but it was honest. It combined design and utility in a way that felt personal and expressive. More than just showing a finished product, I shared the story behind it, the confusion, the connection to my grandfather, the long nights of rewiring and rethinking, and finally, the synthesis of who I am.

REDI Lab didn’t just give me the space to build something, it gave me the time and tools to understand why I build in the first place. I came in knowing what I liked. I left knowing what I valued.

In the end, the greatest success wasn’t the machine. It was discovering that the intersection of engineering and art isn’t just a skill set, it’s an identity. One built from curiosity, challenge, and a deep-rooted sense of purpose.